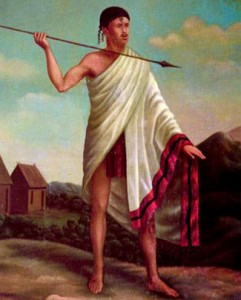

In 1787, Andrianampoinimerina (loosely translated “the king who is not like the stupid” or “the one, who will always stay in the Merina’s hearts”) was chosen by his father as successor to the throne of the Ambohimanga kingdom – that’s at least what legends tells. He was then 42 years old. Historians instead say that a grandson of Andrianjaka, prince Ramboasalama, internalized the throne and henceforth called himself Andrianampoinimerina. Nevertheless, he was the most famous king of the Merina people, and remained it until today.

During Andrianampoinimerina’s reign, many revolutionary innovations were made, for example rice storages for orphans and widows, a new penal code, rules for rice cultivation, street cleaning and social life. For the first time, a part of the forest around the royal hill of Ambohimanga was declared protected under this king. The people was divided into different Merina castes. Andrianampoinimerina’s ambitious aim was to unite Madagascar as one big kingdom. His slogan „Ny ranomasina no valapariako“means as much as “The border of my rice fields is the sea”. Thus he captured the neighboured kingdom Antananarivo in 1794, and conquered the territories of Bara and Betsileo during the following years. Arranged marriages played many families into the king’s hands – he mainly married daughters and grandchildren of his throne precursors. In 1810, Andrianampoinimerina died. His son Radama I., only 18 years old at coronation ceremony, transfered his royal resicende from Ambohimanga to Antananarivo, which made the latter Madagascar’s capital.

Meanwhile, Napoléons defeat bechanced in Europe, with wide-ranging consequences. Great Britain assumed hegemony over the trade routes of the Indian ocean and occupied La Réunion and Mauritius. Madagascar indeed was targeted by France yet. This is way the gouvernour of Mauritius asked France to approve Radama I. als king of Madagascar – this way the island had become sovereign and would have been beyond any claims. Contemporaneously, he sent military advisors to Radama I., who should support him strategically in the batte against Sakalava and Betsimisaraka. In 1817, king Radama I. signed a treaty of friendship with the British delegate Captain Le Sage. Against payment of 1000 $ in gold, 1000 $ in silver, gun powder, weapons and 400 old British army uniforms, he also signed a treaty to proscribe slave trade and embark British missionaries. Radama I. was also responsible for transfer of the former only oral Malagasy language into written papers.

King Radama I. could finally fulfil his father’s desire and conquer (almost) whole Madagascar with the victory over Betsimisaraka people at the eastcoast in 1824. He is alleged to have said then: “Today I own the whole country – Madagascar has a king now!” About 30.000 soldiers helped provide this victory. During his regency, king Radama I. married twelve wives. Only Ranavalona I., his first wife, was called queen officially. In gratitude for her father, who had warned the former king Andrianampoinimerina about a conspiracy, she had been betrothed with Radama I. early. Although she was his first and thus most important wife, Ranavalona I. never beared her husband own children. Instead she spend much time with English missionaries. In the end, the king fathered offspring with his other wives, among them Rasalimo (daughter of the king of Menabe) and Rangita (daughter of prince Andriantsalamanjaka).

In 1828, Radama I. died alongside of his own soldiers, allegedly during a campaign against Betsimisaraka people. Other sources suggest he might have simply died of an alcohol intoxication after an sprawling victory celebration. At the time of his death, only the territories of Mahafaly, Antandroy and Bara people of South Madagascar were not under his reign.

King Radamas I. legal successor according to tradition was Rakotobe, his oldest nephew and one of the first young men, who had learned in the schools of the London Missionary Society. For fear of repressions, the two soldiers, who had accompagnied Radama I. during his last campaign, concealed the king’s death from the public. Thus querrels came up in the royal residence, and rumours about the king’s decease remained unconfirmed for a long time. Ranavalona I., who was called Ramavo yet, meanwhile laid claim to the throne.

Pictures in the slider: Ambohimanga and Andrianampoinimerina’s house today

MADAMAGAZINE Your Magazine about Madagascar

MADAMAGAZINE Your Magazine about Madagascar