What would Madagascar be without its giant landmarks, the mighty baobabs? Over here, they might be known as monkey bread, and have been famous as photo motives and in literatures for centuries. These huge trees, whose roots seems to grow into the sky, enchant everyone, and many baobabs are told to possess magic power. Madagascar has not less than seven different kinds of baobabs – worldwide, there exist only eight species at all. So quite rightly you can say that Madagascar is the country of baobabs.

The African Monkey Bread (Adansonia digitata) is – according to its name – distributed all over the African continent, including Madagascar. Thus this baobab species might be known to most travellers. Its name derives from Latin digitum, which means fingers. The leaves of this species look like a human hand. The African Monkey Bread has a short, but very thick stem and a broad, protruding crown, that looks like a giant mesh of roots. In Madagascar, its home is the western part of the country, e.g. the old baobab of Mahajanga belongs to this species.

But the most famous baobab of Madagascar is probably Grandidier’s baobab (Adansonia grandidieri). The tree giants can grow up to 25 meters, and stay their whole lifetime straight and slender. They can be found in west Madagascar, from Morombe to somewhat north of Morondava. The famous baobab alley between the city of Morondava and a village called Belo sur Tsiribinha mainly consists of this species of baobab, and also the nearby baobab forests of Andavadoaka inhabit several individuals if Grandidier’s baobabs. Although the baobab alley today looks quite bleak besides the trees, Grandidier’s baobabs originally grew in thick dry forests. Slash and burn agriculture and bush fires – baobabs can resist fires because of their thick, up to 10 cm measuring bark – created the savannah of today, that stole the trees their fertilizer.

The third of them is the Malagasy Monkey Bread (Adansonia madagascariensis). This species grows 5 to 25 m in height und stays relatively slender. Despite its name, it is quite rare in Madagascar and only occurs in the northwest of the island, between Antsiranana (French Diego Suarez) until the river of Sambirano. It tolerates even humid environment, and mainly grows on limestone and sand.

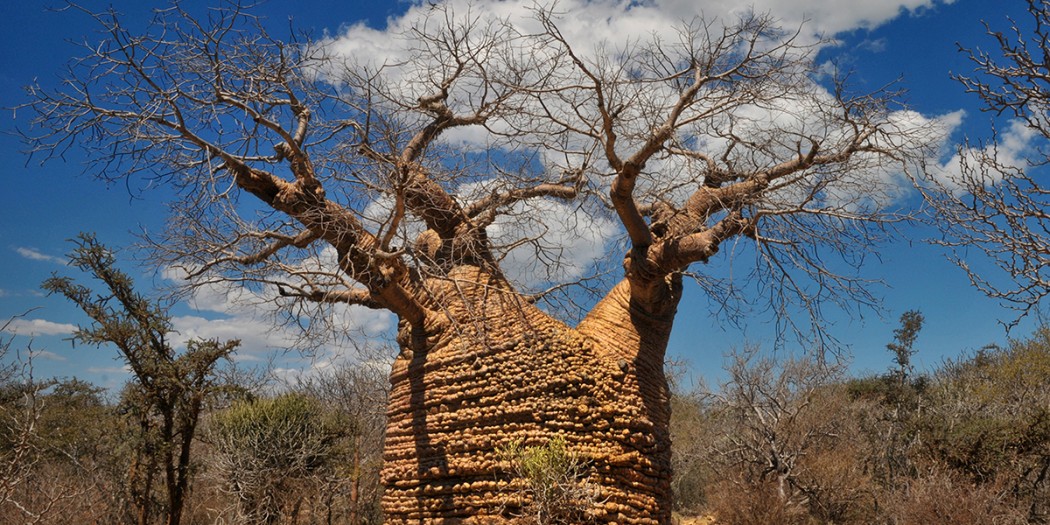

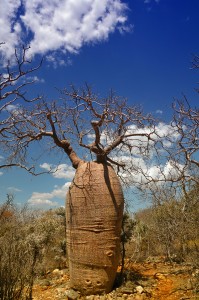

In contrast, the typical baobab of the south is Adansonia rubrostipa, called Fony by the native people. These baobabs grow several meters in width, but do not grow high up in the air. The average height is not more than 12 meters. They typically grow in some kind of bottle shape, with a bizarrely winded crown. The Fony’s habitat is Madagascar’s south west coast around Toliara (Tuléar) and along the west coast in residues of old spiny forests. During rainy season, this species is the only one to build yellow flowers instead of red ones.

A second baobab of the south is Adansiona za. “Za” is a Malagasy expression by southern tribes for baobabs, and found its way into scientifical nomenclature. You can find these trees from the extreme south of Madagascar, e.g. Andohahela national park, until Zombitse-Vohibasia and Isalo national parks and even north Madagascar short before reaching the Sambirano river. Adansonia za grow in a more cylindric shape, and become 10 to 30 m in height. Their home are savannahs and spiny forests.

The two resting baobab species belong to the northernmost part of Madagascar, dry and hot areas: One is Perrier’s Monkey Bread (Adansonia perrieri), of which only very few trees exist. The largest population at the moment is known from nearby the village Ambondromifehy (area of Ambilobe), and consists of less than a dozen baobabs. This species grows up to 20 or 25 m.

The second baobab oft he north is Suarez‘ Monkey Bread (Adansonia suarezensis), named either after the city Antsiranana (earlier Diego Suarez) or its eponymic Portugese discoverer. In the forest of Mahory and near Montagne de Francais, these baobabs stay beneath other foliage trees, but there are not many left of this species. These baobabs mostly stay smaller than 20 m, slender and wear thick, horizontal branches a treetop.

The scientifical name of the baobabs, Adansonia, traces back to French botanist Michel Adanson, who dared an expedition to Senegal in the 18th century and wrote the first scientific description of a baobab tree. Instead the name “baobab” probably comes from Arabic bu hibab, which means as much as “a fruit with much seeds”. This would fit to the fact that people from the Arabic region settled early in Madagascar.

Its whole life, a baobab is slow and leisurely – it is the allegory of the Malagasy people’s life motto: “Mora mora” means “easy going” or “slowely, slowely”, a constantly recurring mantra of the island’s inhabitants. The young baobab plant stays a sapling for 10 to 15 years – although it may grow several meters in height during this time. The tree is still slender and only slightly resembles the typical trees of its kind. At the age of 20 years, a baobab blossoms for the first time in its life. Now the second growth phase begins, and the baobab begins to build its stem that can reach several meters circumference depending on species. Between the 30th and 40th year of life, the first branches begin to grow horizontally and build the characteristic crown. It is time to stop growing in height now. At the age of about 70 years, the third growing phase of the baobab starts. The stem becomes bigger and plump, a bottle shape can be the goal. The 4th phase is the last stage of life for the baobab, it can last many hundred years. In this stage, the baobab grows only few centimeter per year, and exclusively in width.

Most time of the year, baobabs wear neither foliage nor flowers due to the heat. But they indeed can practice photosynthesis like other plants: With a thin layer of bark right under the surface. When rainy season comes, usually around November, the first buds sprout, and by and by, the treetops become green. In only one month, a baobab is in full leaf – only if there is very few rain, the leaf development delays. Blooming usually lasts from February to April, and each of the pink to red flowers is a little piece of art: The bark like outer leaves roll up like a spiral to the back, and thus release the flower itself. Each flower is only one single day in blossom before drying out and falling to the ground.

Baobab flowers are fertilized by fruit bats, lemurs , butterflies and moths. Deeply hidden in the flower, they find the sweet nectar, and unremarked take pollen to the baobab’s counterpart. After few months, the dry season comes again, and the baobabs throw away all their leaves. Now the tree begins to build its fruits, which takes about eight months.

The different fruit of the baobabs are large, hang on pedicles and wear a thick shell covered by some kind of velvet. Inside there are 20 to 40 dark red, rock-hard seeds with the size of a hazelnut each and bedded in fawn, fibrous fruit pulp. The pulp is edible, and tastes a little bitter like tamarinds due to its high concentration in vitamin B and C. In Madagascar’s wilderness, mainly lemurs eat the seeds accidentally with the fruit. This passage through the digestive tract of the lemurs make most seeds more germinable.

Additionaly, some species do a so-called dormancy, during which the seed is only “waken up” again to germinate by a certain event, e.g. ongoing rain or another passage of a digestive tract. This behavior of baobab seeds make scientists face a very special challenge: It isextremely hard to reproduce some species that are already close to extinction. In southwest Madagascar, Ankarafantsika national park owns the worldwide last two baobabs of subspecies Adansonia madagascariensis boenensis. Many efforts have been done to make the seeds germinate. Until now, no trial succeeded, no matter if the seeds were dashed with boiling water, if the shell was scarified, if the seeds were treated with acid or fed to elephants. In 2013, one of the last three remaining baobabs of this species was chopped down by a cyclone. Now there exist only these two last single trees, and still none of the reproducing help was succesfull.

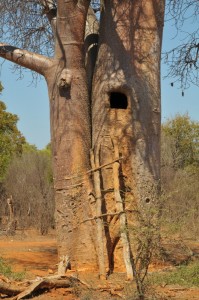

Besides all this, baobabs are masters of water saving. During only one rainy season, an average baobab sucks up to 140.000 liters of water. In the extreme south of Madagascar, people often tap baobab stems in order to get drinkable water, sometimes they even cave the baobab’s stem with a machete to get some kind of dwell. In the areas around Tolagnaro and faux cap, it sometimes rains only few days of the year. There the baobabs become downright life savers. They provide not only water for thirsty people, but also edible roots and leaves, and you can create roofs, huts, baskets and more from the bark. The dried leaves serve as useful medicine against mouth problems, and the leaves are often used against rheumatism and joint pain. In very dry times, the fibrous bark is fed to zebus. In contrast to these useful baobab tasks, the wood of the trees actually cannot be used for anything. It decays quickly and cannot be processed properly due to its elastic attributes.

But in Madagascar, people generally use baobabs not as much as in continental Africa for crafts and meals. This is caused by most baobabs being fady, which means taboo or sacred (or both). Malagasy people call them Reniala, the mother of trees. Several baobab in Madagascar, among them the “mother of the forest” in Tsimanampetsotsa national park, are especially protected, either due to their special shape or a remarkable age. In general, Madagascar’s baobabs have few enemies. In contrast to continental Africa, Madagascar has no large mammals that could destroy a fully grown baobab. The biggest threat to baobabs here is the human being with ongoing settlements, the included destruction of landscape and forests and the slow, tedious reproduction of the baobab. IUCN lists three Malagasy baobab species as “threatened by extinction” (A. grandidieri, A. perrieri und suarezenis), the others are at least „potencially threatened“.

The possible age of baobabs is legendized in Madagascar. The old baobab of Mahajanga is said to be more than 1500 years old. In fact we know today that few baobabs become older than 400 to 500 years. Some botanists assume that baobabs may become up to 2000 years in theory, and that the baobabs of the African continent usually get up to an age of 800 years. But in Madagascar, no one yet tried to examine scientifically the real age of the baobabs. Indeed it is not easy to estimate, because baobabs have no annual rings like normal trees. Nevertheless, today we can be sure from old photographs and people telling it, that some baobabs have been lasting in their place for several hundred years yet. If they could narrate what they have been through and which experiences they made – what would they tell us?

MADAMAGAZINE Your Magazine about Madagascar

MADAMAGAZINE Your Magazine about Madagascar