About 25 kilometres northeast of Antananarivo in the central highlands of Madagascar lays the royal hill of Ambohimanga. The road there is relatively good, but due to the very chaotic and dense traffic in Tana, a drive to Ambohimanga alone can easily take one to three hours depending on chosen day time. If you want to visit Ambohimanga, it is better to plan a whole day.

Ambohimanga simply means “blue hill” in English. It is the most important and highest of the twelve sacred hills over which Madagascar’s capital Tana spreads and 1468 m high. The palace area itself is surrounded by a formerly dense forest belt, which is a remnant of the primary forest that originally existed everywhere in the highlands. First evidence of the existence of Ambohimangas goes back to the 15th century. At that time the place was called Tsimadilo. It was renamed after an early ruling family in Andriamborona and finally named to Ambohitrakanga, which means as much as “the hill of the guinea fowls”.

At the end of the 17th century, King Andriamasinavalona ruled, who gave the hill and its palace its present name, Ambohimanga. Legend has it that he had to pass his empire on to one of five sons. Under the chosen son, King Andriantsimitioviamninandrianadrazaka, several walls, trenches and other elements of fortifications were added from 1710. Most of the later palace complexes and the village of Ambohimangas were extended under him. His son Andiambelomasina followed as regent in 1730, he had 12 grandchildren. The Madagascans tell themselves today that one day he summoned all these grandchildren. He presented them with tempting gifts, and everyone should choose one of them. Only one took the least prominent, a basket of earth, and the wise ruler saw that this would be the right regent for his people.

In 1787 the reign of the most famous king of Ambohimanga, Andrianampoinimerina, began with this story. His dream was to make Madagascar’s tribes and ruling classes a united people. He himself did not succeed in this during his lifetime, but with his many innovations he heralded a new epoch. From Andrianampoinimerina shall come the saying “He who desecrates or destroys Ambohimanga, the same will happen to him by his ancestors”. Under the famous king, representatives of all the clans of the kingdom lived in their assigned huts in Ambohimanga, there were rules for street cleaning, widows and orphans were provided with rice supplies and the surrounding forest was placed under protection. These requirements were revolutionary for Madagascar at that time, and so the name of the king also appropriately means “the one who always remains in the hearts of Merina“. Another translation is “the one who is not like the stupid ones”. From the time of this king and his barter with other countries still cannons are preserved, which carry the initials of the Royal Marines (England).

When Andrianampoinimera’s son Radama I. moved his seat of government to Antananararivo in 1810, Ambohimanga lost its status as the capital of the country. In return, however, he succeeded in what his father had not succeeded in: the unification of the Madagascans under a single ruler. In 1828, with the death of her husband Radama, Queen Ranavalona I. came to power by killing all other potential regents (wives, sons, mother). She ruled for many years, until 1861. Ranavalona I. went down inglorious in history. During the more than 30 years of her reign she tortured and murdered subjects, tried to exterminate foreigners and sealed off her empire against any outside influence. She was followed by Radama II., Rasoherina, and Ranavalona II. The last regent of Ambohimanga was Ranavalona III., who had to relinquish her rule to the French colonial power in 1896.

Today, the Royal Hill has the best preserved palace complex in Madagascar. The centre of the winding complex is the very simple house of the famous King Andrianampoinimerina, which is built entirely of dark rosewood with a gabled roof made of shingles. It consists of a single room without any splendour. Inside five stones form the remains of an open hearth, and the bed frame of the royal couple for their wedding night as well as the loft bed of the king himself are still present. You can also see some old spears, knives and original pots. At half height and directly under the roof of the house there are narrow wooden planks on which the king could retreat in case of unknown visitors. While one of his wives asked the guests, the officially “absent” king secretly listened to the conversation from above. If the guests were allowed to stay or if the king wanted to receive them himself, he threw down a small stone to his wife’s right from above. If you want to enter today, you have to walk with your right foot first, and come out the door backwards with your left foot first – this is what tradition demands.

In the immediate vicinity of the royal house stands the English style weekend house of Queen Ranavalona I., which still contains original old beds, sofas, cupboards and other furniture from the 18th century. Behind the two royal houses lies a series of graves (wooden houses) in which the famous kings were originally buried. They are still used today for small offerings for the ancestors – once slaughtered chickens, today sweets, honey and rum.

In royal times, the northern part of the palace complex was also a court chair (whereby of course, in the end, the king was always right) and the place where new kings were proclaimed. A large stone in the shadow of a sacred tree was used for this purpose. It is said that Andrianampoinimerina was only 1.45 m tall and therefore always needed a “pedestal” to speak to the people. Right next to it is a man-made pond, the Amparihy. It served as a ritual bath, a place where sins were washed away and children were circumcised.

In front of the palace complex itself is a large public square, the Fidasiana. The east facing part of the square was once sacred and intended for graves. The bones of the kings were kept in a specially created house, the Tranomanara. This was demolished in 1897 by the French colonial power and the royal remains were brought to the capital Tana. The aim was to undermine the importance of the former royal hill and to underline French power. Instead, the French built barracks instead of the Tranomanara. Seven years later, all signs of French supremacy were finally removed from Ambohimanga. On the Fidasiana there are still several sacred trees, some of which are almost 500 years old – some local Madagascans even speak of 1500 years. Next to a large, flat, holy rock for the proclamation of royal messages there is a second holy rock, which was and is intended for offerings. In the square next to it, a zebu is still slaughtered every New Year’s, which is then cut up on the rock, prepared and distributed among the assembled Madagascans.

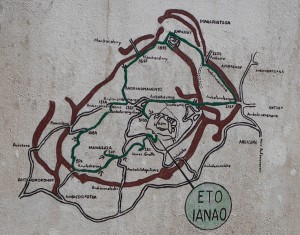

The palaces are surrounded by various walls and ditches, few of which still exist, many of which have been overgrown or decayed by plants for hundreds of years. The outer wall has seven gates, each with its own function and significance, built in 1787. The three most important gates are the main entrances, one in the east (Ambatomitsangana) and one in the west (Andakana) of the wall and the gate of the king, Ambavahaditsiombiomby. The name of the latter means “no cow goes through” and is flanked by two large rocks. Two more gates, Miandrivahiny in the northwest and Amboara in the north, were intended exclusively for the transport of the dead. To the south and southwest are the Ampitsaharana and Andranomatsatso gates, which were mainly used as sentries. The seventh and last gate of the inner wall is Antsolatra.

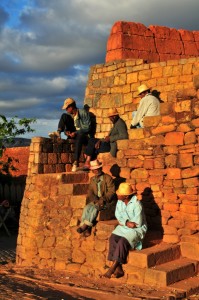

In the time of the kings, each gate was closed in the evening by a huge stone slab weighing tons. Legend has it that the stone in front of the king’s portal had to be moved by up to 70 soldiers simultaneously. Today there are still individual stone slabs at some gates, some of which weigh up to 12 tons. The inner wall with seven more gates was built later. In 2001 Ambohimanga was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is still the most important ancestral place of worship for the Merina people. On certain occasions and seasons they make pilgrimages up the blue hill to honour the ancestors, offer offerings and ask for the blessing of the deceased for the lives of their families.

At the moment the palace complex is unfortunately in a rather dilapidated condition and is visited only by few travellers. Due to the additional long journey there and back, a visit can therefore only be recommended to travellers who are very interested in history. The palace complex is open daily from 9 am to 5 pm, and can be visited for a small fee including a guided tour (duration about one hour). Unfortunately, the visit to the walls of Ambohimanga and the rest of the hill is not included, but you can set off on foot. A site plan for orientation is on the forecourt of the palace complex, one of the large stone gates of Ambohimanga is in the middle of the next village under the palace.

MADAMAGAZINE Your Magazine about Madagascar

MADAMAGAZINE Your Magazine about Madagascar