Madagascar has many different ethnic groups, and most of them still have original lifestyles, ancient traditions and centuries of deep-rooted faith. But a small group of Madagascans live even closer to nature and the lives of their ancestors: The Mikea, Madagascar’s last nomads.

The small ethnic group of about 1000 people gets its name from the forest of the same name in the southwestern part of the country, which lies near Morombe and Lake Ihotsy. The area they still walk through today stretches from there to Manambo, not far from Toliara (formerly Tuléar) in the south. The Madagascans call it Ambany’vohitse, the land under the hills.

Where the Mikea come from or who they descend from, one doesn’t know for sure. First indications of the settlement of Madagascar can also be found in the area of this ethnic group, and it is assumed in many places that the Mikea are descendants of a part of the Vazimba. Other theories suggest that Mikea are people whose ancestors fled to the woods from the Sakalava in the 17th and 18th centuries or later from the French colonial masters. The fact that already in the 16th century different seafarers found people in the area of the Mikea, who resembled today’s Mikea very much, speaks against this.

Today the Mikea share their habitat mainly with the ethnic groups of the Masikoro in the east and the Vezo on the coast. Many Mikea speak the dialect of Masikoro and bear their clan names, but still have many differences to their neighbours, for example in faith or the use of Mikea’s own words, which cannot be found in any other language. They live mostly in small settlements of a few huts and a handful of people under the simplest conditions. Loincloth, old garments and cloths serve as protection from sun and wind.

The Mikea have a recurring annual rhythm that begins in October with the slow rainy season (fasoa/litsake). During this time they sleep in the open air, often a hole in the sand is enough as a sleeping place – you sleep where you are. The people are now in the so-called Kizo. Men and women collect as many tubers as they can, mostly sweet potatoes (ovy) and manioc, whose leaves (cassava) they also use. What is not eaten is kept for later. The Mikea always leave some tubers behind to be able to harvest in the same place again next year.

In November, with relatively high rainfall, the Mikea migrate to their Tana, a small village that is usually located in a clearing in the woods. Depending on the availability of sweet potatoes and manioc, the village does not remain in one place for a long time, but always moves to where the best harvests are to be expected. Around the huts of palm leaves and grasses (Tranofotake with clay or Tranovondro with bast mats) there are narrow fields which grow relatively wild during the absence of their owners. In front of the larger, better fortified huts there are often roofs called Kitrely, which are used both as shady shelters and for storing or drying food.

In the rainy season they go hunting, using Tranoakata, narrow rectangular huts made of grass in many places. With spears and snares, rarely traps, the men hunt for bush pigs, birds and now and then also smaller lemurs. In November or December maize and manioc are planted, the fields provided for this purpose are simply burnt down beforehand. Slowly Tenrecs (Tambotrike) come out of their caves and become the most used hunting object of Mikea. In the forest, people can also collect wild honey.

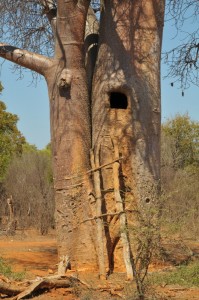

At the end of the rainy season, towards March and April, the time of maize harvest begins. Now many Mikea live in the Tranoholits’hazo, hardly chest high huts from tree bark. In the burning sun of the dry season, supplies are dried and the time of the Kizo begins again. In the midst of the heat, the Tenrecs go into a kind of summer hibernation and thus become easy prey. However, the dry season (asotry) is the hardest time of the year for Mikea. They now follow the best hunting and gathering grounds. Like many other waters in the area, the Ihotsy is a salt lake, and the only sources of drinking water are the Mangoky River and some small ponds and streams in the Namonte area, where the Mikea also live from fishing, similar to the Vezo. They use huts called Tsanosokay, which stand on the beach and change their location depending on the best fishing area. Some of them also leave the land and live on their self-built sailing boats or surrounding islands. Those who live in dry areas, on the other hand, are often thirsty and hungry. Like many people in the South, the Mikea like to use plants to preserve the vital water. Thus one finds again and again drilled Baobabs, from which water is drawn. The Mikea also know a long, thick root called Babo, which tastes like a watermelon and stores enormous amounts of water. For particularly meagre or hard years, the Mikea use the word baintao, which means “the wounded year”.

Like many Madagascans, belief in the ancestors of the Mikea is very important. They have sacred trees, hazofaly (faly here does not mean happy, but is a dialect of fady, so taboo), in which the ancestors live – mostly Baobabs or tamarind trees. Unlike the Masikoro living around them, Mikea have neither tromba (spirits of the ancestors that appear to the living) nor circumcision ceremonies.

Their supreme god is Ndranangahary, to whom offerings such as rum, honey, tobacco or, more rarely, animals are dedicated. Mikea live mostly in family groups, one man has several wives. At about ten years of age, children no longer sleep with their families, but in their own small huts, simple constructions of sticks and a roof made of grass or bark, which is open on both sides. The young men use similar simple accommodations when they travel through the region as herders, to sell their own goods or in search of small jobs.

Even today many Madagascans and foreigners still believe that the Mikea do not even exist. This is partly because their inhospitable habitat attracts few people, and partly because they deliberately avoid strangers. Many Mikea have mixed with the Masikoro and Vezo and live only semi-nomadically in their villages, for example in Vorehe, Andalambezo or Ampalabo. As a result, many villagers separate the Mikea in the real Mikea, the Masikoro-Mikea and the Vezo-Mikea. The real Mikea are even said to flee their villages from strangers in many places. But this impression could also arise from their nomadic lives and the unannounced arrival of strangers at unfavorable times, because many huts are empty during the day and are only filled with life again in the evening. Mikea are often regarded as primitive forest dwellers who always wear dirty clothes and run away afraid of people. In fact, most nomadic Mikea wear their “good” clothes only to visit other villages and not in everyday life. At the same time, their great knowledge of the spiny forest, its inhabitants and plants is highly valued by other ethnic groups. Their healers, the Ambiasy, are considered very powerful in Madagascar.

Since the 1990s, Mikea have been forbidden to continue with their form of maize cultivation (hatsake), which has only been used for a few decades. This is intended to protect valuable forest from further deforestation. Instead, cassava cultivation is being promoted today, in which the fields can be used for longer than just two or three years. Since 2007 the Mikea Forest has been an official protected area, which is even to become a national park in the future. This protection status means severe restrictions on the use of the forest and the surrounding buffer zone. The Mikea themselves are not officially subject to any restrictions, which, however, turns out to be difficult to implement in practice. Who Mikea is or sees himself as Mikea, is very different from place to place and cannot be defined universally. A further complication is that in the western part of the actually protected area a large region has been opened for the mining of titanium, among other things, and since then there has been a rumour among the people that the entreprises want to chase them away.

The RN9 has been running through the Mikea area for decades, and if you are travelling along the road as a traveller, you can find honey pots and other barter goods on the side of the road here and there. You can take some of it, but you have to leave something equivalent in exchange in the same place, for example tobacco, rice, tools or rum. Mikea themselves will rarely be seen. Thus they remain the secret, unknown inhabitants of the rough spiny forests and plains of the southwest – and the last nomads of Madagascar.

-

- Tribal journeys: The Mikea

Jean-Pierre Dutilleux | France 1997 | Documentation | 30 min - Pictures made by Frans Lanting

- Mytification of the Mikea

Journal of Anthr. Research Vol 56, No 2, p. 163 – 185 | USA 2000 | Authors: Lin Poyer, Robert Kelly - An ethnoarchaeological study of mobility, architectural investment and food sharing among Madagascar’s mikea

Amerian Anthropologist Vol 107, No 3 | USA 2005 | Authors: Lin Poyer, Robert Kelly, Bram Tucker

- Tribal journeys: The Mikea

MADAMAGAZINE Your Magazine about Madagascar

MADAMAGAZINE Your Magazine about Madagascar